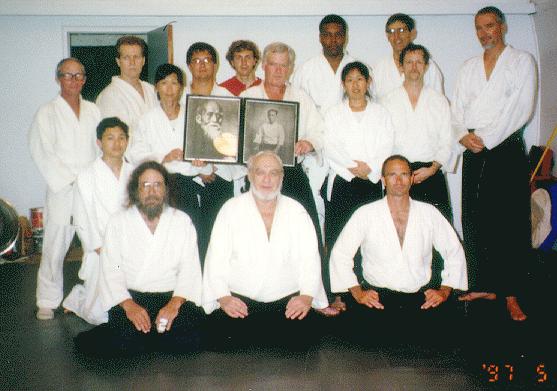

The Windward Aikido Club was founded by Ralph Glanstein Sensei (6th dan). Robert Kinzie Sensei (5th dan) is the Head Instructor. Visitors are welcome and classes are always open to beginning students.

| MONDAY | 7:00 PM - 8:00 PM | Robert Kinzie Sensei |

| 8:00 PM - 9:00 PM | Robert Kinzie Sensei | |

| WEDNESDAY | 7:00 PM - 8:00 PM | Robert Kinzie Sensei |

| 8:00 PM - 9:00 PM | Robert Kinzie Sensei |

Questions regarding classes and location can be directed to Robert Kinzie at 808-235-5943.

Windward Aikido club is located on Keaahala Road, Kaneohe, HI, 96744, one half block mauka from the intersection of Keaahala Road and Kamehameha Highway, on the left side. Look to the rear of the lot for an old quanset hut.

In 1963 Glanstein Sensei moved from New York to Hawaii with his wife and children for the express purpose of studying Aikido. He taught and trained in Aikido until his death on January 27, 2000. Glanstein Sensei's classes offered a wide variety of interesting material which include not only the traditional Aikido curriculum, but also techniques from such disciplines as Tai Chi, jujitsu, wrestling, judo, boxing, fencing and others. Glanstein Sensei also taught some of the old-style ki material which was dropped from most Aikido dojo's when the split between Tohei Sensei and Hombu dojo occured after O-Sensei's passing away. Glanstein Sensei emphasized a soft approach and the use of ki and breath rather than muscle. In addition to the usual arduous and sincere training, Glanstein Sensei frequently included post-training sessions at his favorite Chinese restaurants where he discussed some of the more fascinating stories of Aikido's history in Hawaii. Once a month Glanstein Sensei held a 6:00 AM training at Kailua Beach. Glanstein Sensei was a warm and generous person. He freely give his teaching to anyone who was willing to come learn.His passing was a great loss to Aikido and humanity.

by Robert A. Wilders, from Aikido Today Magazine #54

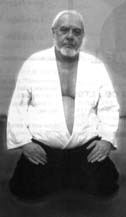

Born in New York City in 1933, Ralph Glanstein Sensei was one of the founding members of the New York Aikikai. In 1963, he moved to Hawaii, where he has trained and taught ever since. Recently promoted to 6th dan by the Aikikai Hombu Dojo, he continues to teach a small group of devoted students on the windward side of the island of Oahu.

Wilders: Sensei, please tell us how you got involved with Aikido?

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: Initially, I was into gymnastics. Then, when I was in my early teens, I became intensely involved with fencing. Then I wrestled and I boxed. In my late teens, I met my first Judo teacher, Charlie Yerkow, who had studied at the Kodokan with Kano Sensei, the founder of Judo. (Even before the martial arts got popular, Charlie said that commercialism was going to ruin them in this country.)

Two of us were coming home from Judo practice, and we happened to see an Aikido demonstration on television. This was in the early days of television, when people would stand outside appliance stores and watch the TVs through the windows. It was a Friday, and we saw a travelogue with two guys who traveled around the world. O-Sensei was on the travelogue. This little guy walked onto the mat, and a whole bunch of young, moosey guys attacked him with sticks, wooden swords. He threw them away like you'd throw away cigarette butts.

Later, I talked to my Judo instructor. "The demonstration had to be phony," I said. "I'm working my tail bone off, and I don't throw people around as easy as that." He said, "No, that's Aikido."

The other kid and I tried to find a place where we could learn Aikido. Not finding any place in New York City, we went to the Japanese Embassy. The people there gave us an address to write to in Japan. We wrote to the address to see whether there were any Aikido dojos in our area. Months later, we got a letter saying that they were delighted we were interested in learning about Aikido and that they would be glad to teach us at 102 Wakamatsu-cho Shinjuku-ku, Japan.

That would have been a rather a long commute from New York. How would I have gotten back to go to work in the morning? But, at the end of the letter, they did say that a student of theirs was attending Columbia University for his Masters in Business Administration. Maybe he could show us something about Aikido.

We contacted this guy - whose name was Yasuo Ohara - and we imposed on him heavily. He said, "Ahhh, Aikido, Aikido. Never lets go of you. Once it holds you, it doesn't let go." We started then, with Yasuo Ohara as our teacher. He was a good teacher, a relatively young guy.

Later, Meyer Goo, who had practiced with all the old sensei in Hawaii, came to New York to learn some advanced communication systems at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. He taught us for a while and, sometime in the early 60's, we had an exhibition of Aikido that attracted many spectators.

The guys who started Aikido of New York City were Eddie Hagihara (who was a 3rd dan in Judo), Virginia Mayhew [See ATM #19], Barry Bernstein, Fred Krase, and me. There was also Lou Kleinsmith. (Having studied Tai Chi, Lou would stand on one leg, and you couldn't move him.) Another original member was a fellow named Fujii - a 4th dan in Judo who worked for the Bank of Tokyo's New York branch. And there was Maggie Newman, who was a dancer (I'd love to find her again). Rick Rowell joined later, around '63. This was all before O-Sensei came to Hawaii.

Over the years I've heard that New York Aikikai started when Yamada Sensei came to the US. The fact is, at that time, there was Aikido in two places in the US: New York and Hawaii. Later, a school was opened in New Jersey. I've read most of the stuff in English on Aikido, but I've never read anything historically correct about how Aikido started in our country.

Wilders: What was the dojo like in those days?

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: We all had to chip in to make the dojo. At first, there was no mat, no gym, no nothing. The dojo was on the first floor of a brownstone with a huge picture window facing the street.

Rick Rowell lived on the second floor in a one room apartment the same size as the dojo. It was a real playboy pad with a fireplace, sunken living room, a big Havana brown cat. I guess Rick wondered what the noise was downstairs. It was us banging and falling.

That old dojo was the first home of the New York Aikikai. We used to practice there every night - Monday through Friday, and Saturday morning. Sunday we'd have seminars. On weekdays, practice would end about 9 or 10 o'clock.

Wilders: Do you know whether any of the other original members of the New York Aikikai are still practicing?

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: I ran into Rick Rowell in California in the 70's, and I believe he is still practicing. I believe that Eddie Hagihara is still practicing as well.

Wilders: You showed me a photograph of Terry Dobson, you, and others at a restaurant in New York. Was it shot during the early days of the New York Aikikai?

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: Yeah, but Terry never practiced with us on a regular basis. He would come by to practice when he was passing through, but he was not a regular New York Aikikai member.

Wilders: What brought you to Hawaii?

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: Actually, I was going to go to Japan. I owned a small milk business in an older neighborhood in Brooklyn, and I had received notice that my entire milk route was going to be torn down for urban renewal. They were going to take my beautiful, sprawling slum and turn it into vertical slums - high rises.

I really wanted to go to Japan, and this seemed like my chance. I could have gotten a job teaching English for about $250 a month, and we could have managed. But then somebody said, "Hey Ralph, if you move to Japan, how are you going to send your kids to an American school?" At the time, American schools cost $1200 or $1500 a year for each kid. So that knocked Japan out of the box. (What I didn't realize was that I could have sent them to school with the kids next door; they could have been bilingual.)

Then Meyer Goo said, "Hey kiddo, you oughtta come to Hawaii. We got great teachers there. We got all the good ones." Ten days after that conversation, my wife, my kids, and I were in Hawaii. The plane landed at 5 o'clock in the evening. I left my family in a one room apartment and, two hours later, I was on the mat with Meyer Goo.

He was right; there were good teachers in Hawaii: Kimura, Ishida, Sukimoto, Yamamoto. I was home.

Wilders: Who was your first instructor in Hawaii?

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: Yamamoto Sensei, I think, was Chief Instructor. My contemporaries were Aoyagi, Yoshioka - those guys. There was also a sub-group of good teachers: Innouye, who was a cab driver, Inuma, who was a close friend of Koichi Tohei Sensei, Goto, Yano, Harry Eto.

The best learning experience was when I had seven or eight classes and a kids' class on Saturday at Waialae dojo. I was an assistant instructor, and I helped teach. So I had seven different teachers in one day. It was like seven private Aikido lessons. That was great!

Waialae was a real gathering place. Meyer Goo has a great deal of knowledge, and I learned a lot from him. But there were many others.

Like Koa Kimura - When my wife met Koa she said, "He's a sweet old man." I thought, "What do you mean he's a sweet old man? On the mat, he's a murderer." I was the only person who remained an uke for him, because he was so deadly. He didn't have to use force. He was always in the best position; force was generated by the position of the two bodies. And he had perfect timing. Koa Kimura always said that "timing is everything." He was great.

Wilders: What work were you doing while practicing Aikido?

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: I was working at Job Corps as a resident worker, and I was also driving a taxi at night.

Once I took the training squad of Job Corps to see Aikido. One trainer was a psychiatrist from Stanford. He was intrigued by Koa. He wanted to take Koa and me to the mainland, hook us up to machines, measure our brain waves, alpha waves, beta waves.

Wilders: When did you decide to go to the University of Hawaii to become a lawyer?

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: I went back to college as a part-time undergraduate student in January 1967. I received my Bachelor's degree - finally - in 1973. Then they opened the law school. I had the hots for that but, in law school, I would have to be a full-time student. I had earned an 'A' average working full-time and going to school part-time. But law school demands your total time. So instead, I enrolled in a graduate program and received my Master's degree in 1975. In 1976, I did start law school, and I graduated in 1979 with a Juris Doctor degree. I spent 12 years on campus. I hated campus. I hated it.

Wilders: I understand you once practiced with Suzuki Sensei on Maui.

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: Every two years, we would have an Aikido instructor's seminar. Each seminar would be held on a different island. In '64 we went to the Big Island.

At that time, there was the practice of jizen. If someone died, everybody would chip in and give money to the family. Suzuki [See ATM #8.] got up and said, "Look, if the father-in-law of one of the Aikido club members in some small dojo in Mountainview dies, why should the members of Aikido all across the state pay money? They don't know the guy's father-in-law. They don't even know the guy. The Hawaii Aikikai is a big organization. If the local dojos want to do something, that's fine. But it shouldn't be incumbent upon the rest of us." What Suzuki said made sense to me. I raised my hand, stood up, and agreed. I made a little speech. I began to feel all the eyes of all the strict traditionalists on me. Oooh. I slumped down.

After that, I couldn't get to shodan. I think that politics kept putting it off. If it weren't for Koa walking in at the test and saying "Give him a shodan!", I still would be ikkyu I hold the record for more ikkyu certificates than anybody in the world: eight.

Once, when I was recruiting for Job Corps, I was sent to Maui. I used to go to the local police department to get the names of kids who might be likely Job Corps candidates - kids who were starting to get in trouble. Suzuki was with the police department, and I practiced with him in the beautiful Lahaina dojo. After practice, he said, "Now, haole boy, we drink." He meant whiskey. He filled up a huge glass for me, and he poured out a shot for himself. That went on for quite a while. I don't really know how I got back to my hotel, but I do remember waking up in a car in the parking lot in the morning. I never made it to my room that night.

Later, I saw Suzuki, and he told me that he had sent a police officer to follow me and to make sure I got back to the hotel safely. What good would it do to follow me? The policeman could have watched me get into an accident.

Wilders: It sounds as if Aikido in Hawaii was one friendly group.

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: Through seminars, we would help the smaller islands like Kauai and Molokai financially. That was nice; it kept a close group.

But then came the Schism [between Koichi Tohei Sensei and the Aikikai- Eds.]. After that there was Aikido-with-ki and Aikido-without-ki. The attitude was "If you talk about ki, you're not loyal to Hombu dojo." In the seminar we just had, the teachers didn't talk about ki or the one-point. Those are Tohei things.

Wilders: You mentioned the Schism. You were there. What happened?

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: It occurred at the celebration of Doshu's birthday at the Oceania Floating Restaurant. Koichi Tohei Sensei was there on the stage with the microphone. Bob Kinzie, who is now my assistant instructor, was sitting with me next to the stage.

Imagine! You're always teaching about Aikido philosophy, and the guy who's the main proponent of that philosophy seizes the microphone and pronounces, "I am the Chief Aikido Instructor all over the world." Then Tohei made another comment, and I recall him pointing to his right toward Yamada and Kanai who were standing with Doshu.

That night, a meeting was called. It was secret, and I didn't want to go. Many of us went over to Doc Wakatake's house. (Doc Wakatake was the president of Hawaii Aikikai.) Later that night, I wrote a letter to Yoshioka, saying that we supported Hombu dojo. But those guys had already decided that they wouldn't follow Koichi Tohei.

At the time there was no Ki Society. Nobody knew what was going to happen. All we knew was that Tohei had quit. Essentially, that's what had happened: he quit. After the split, we wouldn't talk about one-point or ki. If you mentioned these things, people looked at you as if you were a traitor to Hombu dojo.

Wilders: What is the story about you being plagiarized?

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: I used to write to a criminologist in California about Aikido, and I began to find my letters appearing under his name as articles in professional journals. "Aikido Rehabilitation in Juvenile Delinquency - that looks like my letter to what's-his-face!"

Wilders: Will you tell the story about explaining Aikido to your father?

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: My father always said, "I don't see how a big fat horse like you can move like that." I'd always say, "Hey Pa, it ain't me - it's Aikido. It doesn't matter how big you are." But he didn't understand. He was a real New York guy.

In the mid '60's he came to Waialae Dojo and watched. After class, I sat with him and Yamamoto. The dojo was empty. I told Yamamoto Sensei that, for years, I had been trying to explain to my father what Aikido is. Yamamoto - who had a round face with a "rice bowl" hair cut - looked at me and he nodded his head. "Mr. Glanstein," he said to my father, "hold my wrist." My father was afraid he was going to get hurt. I said, "Pa, go ahead." He held Yamamoto's wrist, and they stood there for 8 or 10 seconds. Then they looked at each other, and they both started laughing. Yamamoto said, "Do you understand?" And my father nodded. He did understand! Somehow, ki had been transferred - or something. I don't know. I can't explain it. But, after that, my father understood Aikido. I've been teaching a long time, but I don't know how to teach that way.

Wilders: What sort of daily training do you do now?

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: I still do the sword. Before I even take up the bokken, I sit in my chair and try to get my breathing down. Koa told me to do that. He used to say, "You do that every day, haole boy, you be strong like hell. Strong like hell." He told me to do deep breathing every day for five years, and to start the five years over again if I ever missed a day.

After two and a half years of daily deep breathing, I missed. That was horrible! It was so hard to do something everyday, not missing a single day, and then - to start again. But I haven't missed daily practice with the sword in a quarter of a century. I still haven't got it right.

"You gotta charge them something for Aikido, a trainer at a Marine base told me. But gurus in India were beggars. They didn't sell their knowledge, because they viewed it as priceless."

Wilders: At one time you taught Marines. What was that like?

Ralph Glanstein Sensei: I had a class of about 40 or 50 Marines during the Vietnam War. I would train them for 3 or 4 months, and then one night I would walk into the dojo and there would be only 6 guys. Then I'd start all over again. It was troop rotation, and it became discouraging.

A trainer on the Marine Base once asked me why I didn't I take any money. I explained why I teach. He said, "If you don't take money, they're gonna think it ain't worth nothin'." To me this is convoluted thinking. "Well, you gotta charge them something." I thought, OK, I'll charge $2 a month for dues. At the end of the month, we took all the money and had a beer bust. Gurus in India were beggars. They always did something to get their daily bread; they didn't sell their knowledge, which was priceless. Once you put a price on it. . . .

As you know, that's the way I feel about Aikido.

This article is reproduced here with the kind permission of Jeff Glanstein and John D. Schleis, General Manager of Aikido Today Magazine.

Sensei. To my brothers and I, when in practice, Ralph Glanstein was "Sensei." Now, 38 years since my first introduction to Aikido, the reality of how Sensei was Sensei off the mat and outside of the dojo, and in every moment of our lives is striking home deep in the core of my being. "Koa," Kimura Sensei, and I recall Yamamoto Sensei saying similarly, "Soft outside, strong inside." Sensei would constantly refer to this maxim. Only Glanstein Sensei was different.

I merited to grow up with this sensei. Sensei, albeit in his youth strove, and achieved, great perfection in his outer strengths and abilities, literally undefeated in fencing and other contact pursuits this outer strength was accompanied by an internal void. Sensei's pursuit of lofty senseis led him and our family far from the proximity of an extended family to a land 6000 miles away. Recently admitted to as the Fiftieth State of the United States, Hawaii was rich in Aikido and other martial arts. Sensei was in his element; he dedicated his free time to Aikido and, indeed, he lived and breathed Aikido.

When at Johns Hopkins Medical Center with Sensei and keeping "watch" one night I realized that I had forgotten the feeling to sleep so closely to him; Consciously and subconsciously monitoring his breathing, waking at the slightest "abnormality." Nary a rest of a ten minute span did I get when Sensei would take a deep breath, stop, hold it, savor it as a deep sea diver, and about a minute or so later slowly exhale a finely engineered, passing of spent air, a full two to three minutes later he would resume the pattern of familiarity. In his sleep he breathed the deep breathing and concentration of his practice.

Although for some time he was a milkman, other times he drove a taxi, and lastly, as a practicing attorney in Kailua, Oahu, Hawaii, his time was always open for others and he opened his home to allow others to bask in a familial setting, to become part of our inner family. He befriended and helped many people through his wisdom, experience, and Aikido, to direct people along a nonviolent path, a smooth path and one comfortable to travel. So, I knew armed robbers, rapists, thieves, runaways, and other "dregs" of society. To Sensei, he saw inside of them and saw a merit. He extended to them a chance to grow and better their own lives. In many, many souls did he affect a change.

His main product was never dairy, nor legal advice. Rather the commodity that he had he gave away freely was one that he was so well endowed as an unending spring constantly spews forth water, Sensei gave of his unending love and allowed others to drink from the deep well that he harbored. "Soft outside, strong inside" overcoming many obstacles along the way. As his inner strengths increased his outside became more and more soft and gentle. Yes, his outside was once tough, but you could only appreciate that toughness if you merited to experience the inner self.

My father was most fond of the tractate of Talmud that dealt with ethics. Throughout the Talmud there is much devoted to the proper behavior of a man and neighbor. While delivering the eulogy at his funeral the passage of Rabbi Gamliel came to my mind. Rabbi Gamliel said, "Any student who's interior is not as his exterior should not be allowed entry to the Study Hall." At first we would think the emphasis is on the exterior, however, after further scrutiny, I believe the real focus was on the interior of a person. When you place your major concern on purifying your inner self then your outer image of consequence will become less of a concern. Such a person was always welcome to the study hall. Rabbi Gamliel in de-emphasizing the outside allowed people to look inside. In so doing your exterior becomes a true reflection of what the inside is. It is only when we make a show and display an exterior that misrepresents our inner personality that Rabbi Gamliel wished the de-emphasize the exterior and require that there be an equal representation on the inner level. Sensei's concern with his outward appearance was nil. The idea of property value based upon appearance and locale was foreign to him. Any visitor to our home can attest to the fact that on the exterior there was no falsity. The true beauty was upon entering Sensei's inner circle, into his confidence, and ultimately into his home and amongst family. In this humble home was always found love and a rare found harmony in today's hectic world.

On 31 January, after taking much care with the prestigious job of preparing Sensei's body for its final internment, dressing him in his gi and hakama (the hakama was previously "Koa" Kimura Sensei's, who bestowed it upon Sensei upon achieving SanDan, many years ago), proper shrouds as he had requested as befitting the traditions of his ancestors, I placed lastly his bokken and tanto alongside him. We then prepared for the solemn ride to his chosen plot in Mililani. Amazing that it would be Mr. Ken Ordenstein of Ordenstein's Mortuary, who would merit to chauffeur Sensei and I across the island. In conversation with Ken, he discovered that his own daughter had been a student of Sensei's for six or seven years. Mind you, Sensei never let himself ride in the back, so this was a very difficult ride. We received no complaints along the way, however. After the traditional funeral and a heartrending eulogy, my nephew Kalani, Ken, and I, returned to the Windward side of the Island. Ken drove. I said, "Ken, you want to see something? I'll show you something real quick if we have the time." He said he was willing, "Anywhere you want to go." We entered my parents' neighborhood. "Ah, I know this place, all the kids learn to drive here." We stopped in front of a wild, overgrown lot, a house parked in the middle but only twenty-five feet away, barely visible, a circumstance due to the wild vegetation. "Hey, I know this house!" Ken exclaimed, "This is the Jungle house!" I turned to Ken and replied, "Now you know the story; It's no longer 'The Jungle House,' it is 'The House in The Jungle,'" Ken understood.

We all understood; All of us who appreciate the "Strong inside and soft outside." That "house in the jungle" was Sensei's citadel, a testament to his perspective and keen insight. This is part of the legacy that my father, and Sensei, bequeathed to his family, his followers, and the world